A hatchet is a small axe, designed for use with one hand. Hatchets usually have slim profiles, meant more for biting deep into wood on the cross-grain than for splitting.

While a hatchet or axe can be used to split wood, their slim profiles tend to get stuck more often. The added weight of the maul also helps to carry it through stubborn logs that would resist even the stoutest blow from an axe.

Table of Contents

What is a Hatchet?

A hatchet is a small axe, designed for use with one hand. Hatchets usually have slim profiles, meant more for biting deep into wood on the cross-grain than for splitting.

Hatchets are smaller than axes, which are meant for use with two hands, and often have about twice the head weight. Axes and hatchets share the same biting, sharp shape. Axes see the most use in felling trees.

Splitting mauls are the largest of the class, they’re basically a wedge on a stick, with the weight of a sledge hammer behind them. As the name suggests, their primary function is to split firewood.

What’s the Difference between a Hatchet and a Tomahawk?

Tomahawks are another small axe, with heads that are often lighter and thinner than those of hatchets. The biggest difference between the two is the way the head is “hung” on the handle.

A tomahawk head is friction fit onto a tapered handle without any wedge to hold it in place. The eye of the tomahawk head is tapered in one direction, wider at the top and narrower at the bottom.

This arrangement allows for easy disassembly, as well as easy replacement of the handle. Tomahawk handles are viewed as consumable, especially in throwing.

Ideally the handle will pop loose instead of breaking, but if it does break, a new one can be made quickly and fitted on.

Hatchets are hung like full-sized axes. They use hourglass-shaped eyes and a wedge to lock the handle in place.

Hatchet handles are not meant to be replaced often. They are much more heavily contoured for efficient strokes. That extra effort in shaping isn’t worth applying to consumable handles.

The head of a hatchet is usually about 1.5 – 3 lbs of steel, whereas a tomahawk ranges 1 to 1.5 lbs. Hatchets keep more of the steel back around the eye, creating a longer “collar” to firmly lock onto the handle.

Hatchets almost always have squared-off polls (back faces) suitable for light hammering of wood or for being driven through things like a wedge. Don’t try hammering nails with a hatchet though, unless it was specifically designed to pound nails, the poll is soft steel, and will be dented by the nails. Tomahawks aren’t built to grip the handle as well, and are more weight-forward for aggressive strikes.

Should a Hatchet be Sharp?

Hatchets should be kept with a keen edge, but don’t go re-profiling the whole bit.

“Sharpness” of a blade depends on the shape of the grind, quality of the steel / heat treatment, and keenness of the edge.

Grind

The grind is the shape of the cross-section, and in general, the thinner the edge of the blade, the sharper it can get.

However, on striking tools, that edge needs some support. Depending on how brittle or ductile the material is, a very thin edge that’s struck will shatter or roll over, neither of which is good.

The convex grind used in axes leaves a little more material supporting the edge to prevent either failure. That leads us to the apple-seed or convex grind shape, which sweeps in from thick material down to the thin edge.

Heat Treatment

Steel is a wonderful material in that it can be heat treated. By heating steel up to high enough temperatures, the carbon that makes it steel instead of iron becomes dissolved and very dispersed throughout the material. Cool steel down quickly from that state, and you “freeze” the carbon in the dispersed state, called martensite.

Martensite is very hard and very brittle. While we like the hardness in blades, brittle is bad. Bend your blade just a little at this stage, and it might be okay, but go just a bit to far, and it’ll explode with absolutely no warning.

To come to a usable blade state, one that will bend a little instead of shattering, we need to temper the steel. Tempering involves heating the steel to a lower temperature than was used in the quench to allow some of the carbon to migrate around to a more relaxed state.

Heat any quenched steel too hot, and you’ll allow all the carbon to go back to its default “annealed” state, softening the steel. This is why sharpening with angle grinders and other aggressive abrasives needs to be done very, very carefully, with lots of breaks to cool it down.

Harder steels take sharper edges, but they’re also more liable to shatter without warning.

Keenness

Keenness is how polished the edge is. You can have a perfect edge geometry (grind) and heat treatment, but if the edge isn’t smooth and well polished, it won’t be sharp.

“Sharpening” an edge is really just keening it up, polishing a very smooth fine edge on it. I use mill files to get a big axe or really messed-up hatchet close, then diamond plates to polish it up well. If I’m really looking for a sharp edge, I’ll polish it on a super high grit waterstone until I can see myself in the bevels.

What is a Hatchet Made of?

Hatchets usually have wooden handles with steel heads, though there are some with fiberglass, plastic, or steel handles.

My first hatchet was a 14″ Camping Hatchet with Forged Steel Construction & Genuine Leather Grip that I used for several years, until a rivet blew on the old leather sheath / mask. Replacing the sheath would have cost as much as the hatchet itself, so I upgraded to a Hults Bruk Almike, and have loved the wooden handle ever since.

The best handles are made from Hickory, which can take a real beating, but absorbs shock well. Ash and Rock Maple are good woods as well, with Ash absorbing more shock than the hickory or maple.

Steel for axes should be selected with impact in mind. I pick 4140 steel for axes and other edged striking tools, it’s a good impact-resistant medium carbon steel. Knives often tend towards the high-carbon end of the 1000 series, 1085 being frequently used, but those are very brittle for striking tools.

How long is a Hatchet Handle?

Hatchet handles normally range about 12″ – 18″. Small “hand hatchets’ may have handles down to 8”, and cross-over forest axes like the Gransfors Bruks Small Forest Axe range up towards 20″.

Why is a Hatchet Handle Curved?

This one actually took quite a lot of digging to uncover a satisfactory answer. According to an article and diagram on Axe Connected, the effect of the curved handle is to magnify the influence of small wrist tilts on the angle of the blade. Their diagram shows some geometric diagrams explaining this, pulled from an old axe book.

In essence, the offset of the axis of the handle to the axis of the grip at the end means more deviation from the same wrist tilt. I picture this as similar to the effects of a shorter sight radius / barrel on a gun, making for far larger changes in trajectory from a millimeter misalignment.

It seems the longer the handle on an axe, the less likely it is to be curved. The offset would get unwieldy with a splitting maul, certainly, but the need for such magnified control over the blade also diminishes with longer axes.

One other byproduct of the curve is the change in blade alignment to your hand. If you frequently split wood with your hatchet on a raised splitting stump, then you’ll want the blade to be aligned horizontally when you strike the top of the log.

Handle curvature can help ensure the blade hits horizontally while your wrist isn’t torqued at an uncomfortable angle.

How do you use a hatchet?

A hatchet is made for use with one hand, but adding your second hand won’t hurt. It can add power and stability.

Hatchets are mostly used like small axes. Cut, split, and limb with them. To get accurate with a hatchet, my old mentor had me cut a dent into a log, then stick a strike-anywhere match standing up out of the dent.

He told me to try to split the match with the hatchet.

I was swinging at matches for a while, and snapped off a lot of matches before I succeeded.

One of the biggest tips for power with any splitting tool is to aim for the top of the splitting stump, not the top of the log you’re trying to split. This slight mentality shift makes a world of difference in the subtle slowing of your axe before it hits the wood.

What is a hatchet good for?

Hatchets are great for splitting down kindling and limbing small trees. This is their design niche, where they’ll outperform any other axe.

Specialized hatchets designed for wood carving work fantastically for all manner of carpentry and fine carving tasks, from framing log cabins, to hollowing out dugout canoes.

Standard hatchets can also be pressed into service on larger or finer tasks. Over the years, I’ve used my hatchet to:

- Fell trees up to about a foot in diameter, though it takes longer than with a felling axe.

- Split nasty, snarled-grain, large diameter logs, though it’s tougher than with a splitting maul.

- Carve a Greenland Kayak Paddle for my wife, though I got a few more blisters than I would have with a band saw and plane. Check out the video and article on that experience here.

Backpackers don’t have the space or the weight to carry a whole tool shed with them on the trail, nor do preppers have room in their bug-out bags. If I had to pick a single tool to bring with me into the wilderness, I’d pick my hatchet over everything else, including my knife.

A hatchet isn’t the best tool for felling, bucking, splitting, or carving. But it will do all of them reasonably well.

Can you throw a hatchet?

I wouldn’t throw my hatchet. Tomahawks are much better suited. The natural “fuse” of the friction-fit handle helps to prevent breakage, and the handles are easily replaceable.

Hatchets are more expensive than tomahawks, for the same level of quality. Throwing is brutal on a tool, and hatchets just aren’t made for it.

The steel used in tomahawks is frequently pretty low carbon to add durability, in exchange for sacrificing some sharpness. Tomahawks will dent and bend under blows that would chip or shatter a hatchet.

You’ll notice that places like Bury The Hatchet use specialized all-steel hatchets for throwing. I wouldn’t want to spend a day splitting kindling with their hatchets, but I’d rather do that than throw mine.

Can a hatchet split wood?

Hatchets excel at splitting small splits of kindling from dry, straight-grained wood. They can be used to split much larger logs though.

To split a large or difficult log with a hatchet takes some practice. There are three techniques that help with the tough logs: weakening blows, upright smashing, and inverted smashing.

Weakening blows work best for knotted, snarled wood. Go ahead and try to split the log as best as you can, but when the blade gets stuck partway through, wrench it back out. Repeat, offsetting your strikes this way and that, rotating the log if you can.

Flip it over and strike from the bottom, continuing to rotate. Eventually a split will find its way around the knot.

To use upright smashing, start the same way as before, burying the hatchet deep into the log. Once you get the blade to stick, lift the log and hatchet together as a unit, high over your head.

Pretending that the log is an extension of the hatchet, slam the whole assembly down onto the splitting stump. Then, drive the hatchet through the log as far as you can, and repeat.

The inverted smashing technique is the last straw. For large, heavy logs, the inertia of the log is more than the hatchet. Bury the blade, then flip the log and hatchet over, so the poll is resting on the stump, and the log is up in the air.

Lift the log and hatchet high, and slam them down. The log should drive itself further onto the hatchet, splitting in the process.

What’s the best hatchet?

I’ve had the good fortune to try many hatchets, but can’t claim to have tried them all. My first was an Estwing 14″ Camping Hatchet with Forged Steel Construction & Genuine Leather Grip that I loved for years, but I’ve since given up on anything without a wood handle.

To me, the best hatchet is one made from quality steel, with a hickory handle that fits my hand well, and a nice balance.

For the trail, I prefer a lighter hatchet. But if you anticipate doing loads of felling and splitting, a Gransfors Bruks Small Forest Axe may be more your speed.

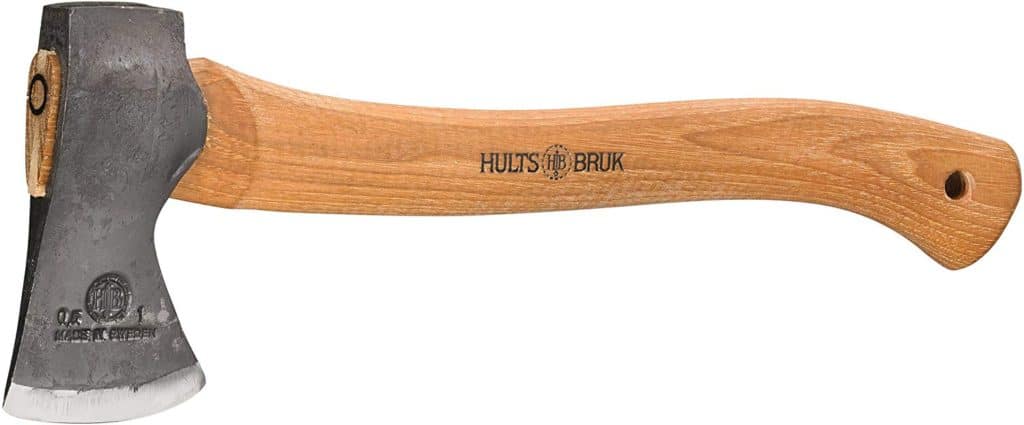

Hults Bruk Almike

This is my current favorite hatchet. Last summer, a large tree (about 4 different 1′ diameter trunks) fell across my driveway in a storm. I had to cut my way out with just this hatchet.

It got the job done pretty quickly, and with minimal blisters to boot.

This hatchet fits my big hands great, and my wife enjoys it in her much smaller hands as well. It came shaving sharp out of the box, and holds the edge well.

I do have to admit that the bevel grind is mismatched on my model, and several Amazon reviews claim this as well. It’s an odd hiccup, but I’ve never noticed it giving me trouble in use.

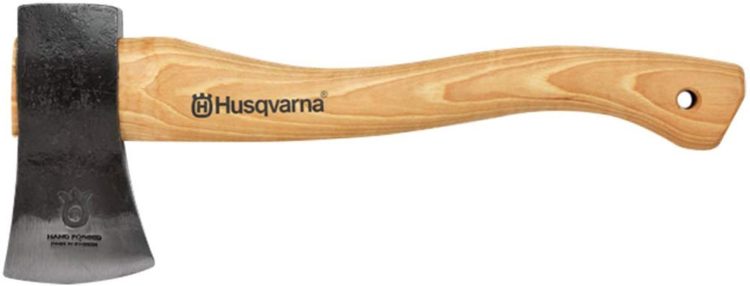

Husqvarna 13” Wooden Hatchet

Half the price, and about the same quality. The only real trade-off here is weight. The head of this hatchet weighs about 1/3 more than the Almike, and you can see it in the profile.

Husqvarna private labels Hultafors axes and imports them into the US. Hultafors has the same great Swedish quality axes as Hults Bruk and Gransfors Bruk boast.

If you’re planning on car camping or picking up a hatchet for the cabin, this is the one I’d recommend.

Conclusion

Hatchets are extremely versatile tools. They’re a jack-of-all-trades in the outdoor world, and I would pick my hatchet over any other single tool for survival.

If you haven’t yet seen me Carve a Kayak Paddle with ONLY a Hatchet, go check it out! That project was meant to show the many ways a hatchet can stand in for fine woodworking tools, as well as demonstrate how to fashion a paddle in an emergency.